It is May 1968, and I am lonely and confused. I am in the middle of a 10-day training program known as a T-Group – or a Human Relations Training Group. I am at a YMCA Conference Centre on Lake Couchiching, north of Toronto, in a group with 12 others.

T-Groups had grown out of the work on social relations (particularly anti-authoritarianism and anti-racism) that was being done in the US by social scientists, some of whom had fled Nazi Germany. By 1962, T-Groups had evolved and were being offered to corporations, social agencies, and the general public as leadership training. The belief was that leaders needed to be able to work in a participative fashion, needed to relate to others, know themselves, and know how they were seen by others.

A T-Group is a group without an agenda or task and without a traditional leader. The group needs to solve the issues of what to do and how to act in this somewhat absurd situation.

I had been in shorter group programs and had studied group dynamics as a student. But I wasn’t prepared for the depth of confusion I felt when I had to face that – after a good beginning, I no longer knew what to do. I wanted to feel better and learn about groups. I thought I knew enough about groups that I wouldn’t be faced with profound or difficult questions. Yet, the T-Group is intended to place participants in exactly that situation—to be in a strange place and not know what to do.

At the beginning of the group, my participation was mostly analytical, commenting on how norms are forming or who had influence. Within a few days, this wasn’t gaining a lot of attention or connecting me to the important currents of the group which seemed to be about deepening interpersonal relationships. Things had changed and I hadn’t. I just didn’t know how to be in this deeper flow of relationships. Hence my confusion and loneliness.

I tell this story because, as mentors, we are often in this space of not knowing how best to contribute to the discussion.

T-Groups and Organization development

I also tell this story because T-Groups and having to search together for answers were foundational to what became known as organizational development (OD) and one of the most important keys to how I understand mentoring.

There was considerable research to indicate that T-groups were transformational experiences for many people, but research also showed that people were often unable to bring their new insights and behavior to the organizations where they were leaders. Existing organizational cultures were hostile to ideas of power sharing and participation. Eventually, as attention moved to the problem of how to bring learning from T-Groups to changing organizational norms around power and relationships, this emerging technology became known as OD.

What came to OD were T-Group technologies like the residential workshop, the focus on understanding power and relationships, and perhaps most importantly, the belief that we did not know the solutions for any particular situation but that we could work them out together in a participative way. What was new was the focus on the system as well as individual learning. What was also new was the idea of “action research”. An important early stage of an OD process was a data collection phase regarding key variables associated with questions of power, participation, and the nexus between relationship and organizational effectiveness.

Interestingly, the purpose of this data collection was not so that experts could propose solutions. The data were “fed back” to the organization so everyone could make sense of the data and build a collective understanding of what was happening. Finally, OD practitioners realized that change would not come from one great residential workshop but would take time (years, not months).

At least in the early days, OD was about:

- A search for solutions that made sense to the people involved; the idea was that the process would create space for people to test out ideas and learn about change by doing.

- A challenge to power and traditional leadership.

- A reliance on participative learning, including the use of small groups and power sharing.

- The use of action research methods.

- Focus on system change, particularly norm change.

It is important to note that, as OD became more popular, it often strayed from its foundations. For example, many projects focused more on organizational effectiveness and profits and less on norm change regarding power and inclusion.

Individual Learning and Transformation

At the same time (late 1960’s, early 70’s), there was considerable thinking about how learning happened at the individual level. One of the big ideas was “experiential learning” as described by David Kolb, an American researcher. Kolb developed what was to become a very influential model of learning. Kolb believed that learning began with the learner’s experience and a need on their part to solve a problem. This led to a collection of information related to the problem, then a sense-making process, and finally action.

What is important about this (at the time) radical understanding of learning is the focus on the learner, not the teacher. The learner has to make sense of experience and build some new understanding that leads to action.

The Place of Respect

The final piece of this puzzle came alive for me in a discussion with colleagues after a not-terribly-successful Employment Equity training program in 1981. The program had benefited from lectures from global leaders, a simulation that engaged the executives in real experiences of managing for equity and intense, challenging discussions. Why didn’t this work better? One of my colleagues said “the problem is that we didn’t really respect these guys (the participants). We treated them as objects to be changed.” I immediately knew this was true. My mind flashed to Carl Rogers, a pioneer of humanistic psychology. Many years prior, he had emphasized the importance of what he called “unconditional positive regard”. If transformational learning was going to happen, then it required a relationship charged with acceptance and deep respect.

Mentoring and IDRC

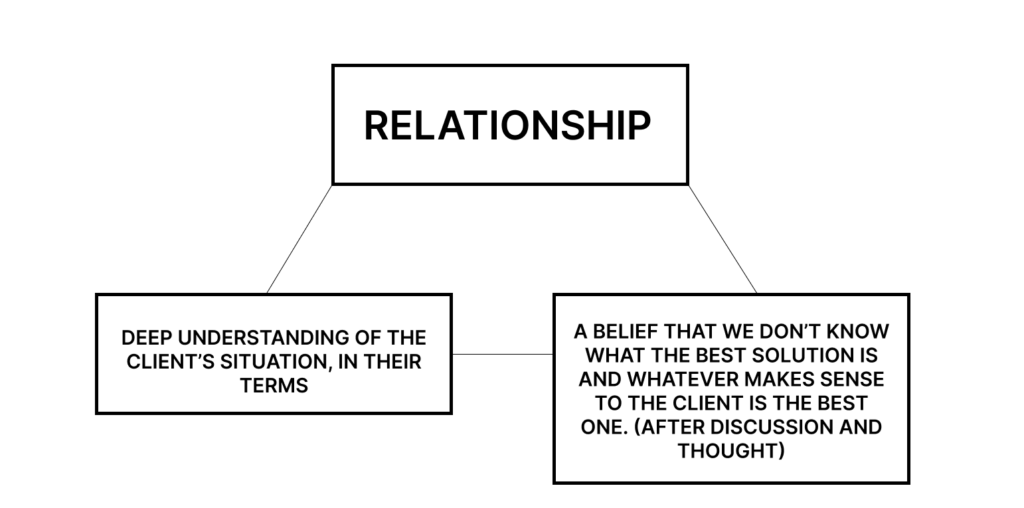

All of these ideas came together when Gender at Work started working with IDRC in 2016. At the time, there was considerable experimentation regarding what is the role of the mentor. After some thought, I believe that an effective approach to potentially transformative change can be summed up by the diagram below.

This understanding begins with the idea of a relationship of respect and an ability to understand the problem and its context in the terms used by the mentee. A mentor can be of help in defining this problem and shaping it but it is important not to make the mentor’s definition paramount. This needs to be a truly collaborative process. Once this level of understanding has been reached, the mentor can bring ideas, opinions, reading, and conceptual frameworks to the conversation, but their value is defined by the mentee. It is her problem after all and the process and the solutions need to make sense to her and be owned by her.

This is not easy—we often work in the moment to respond to what the mentee is saying and thinking. We can’t show up with a slide deck carefully developed beforehand. We are often working in an area we don’t understand and feel the need to demonstrate our usefulness.

The following quote from an excellent Gender at Work Associate and facilitator, Nkechi Odinukwe, is representative of what we can feel.

The next day, I made it to their office and stepped into a room filled with people - they were nice and welcoming, but they were mostly from academia – professors, Ph.D. holders, postgraduate students, and experts in various fields. They also had a gender expert as a member of their team and one of them had just returned from a gender conference held in the global north. Even though I knew Gender at Work is renowned for its unique approaches and methodologies that work to support change for gender equality, I experienced some apprehension knowing that individuals here are experts in their field. I had to deal with how to continually unlearn what society has taught me about such spaces – so as always, I leaned down within myself to pull up Gender at Work’s principle which holds me up as a learner rather than an expert and that helped pave the way for this journey to start.

This quote really communicates what it feels like to be expected to deliver expertise but not want to live up to that expectation. Instead, to be open to what the situation is telling us and find a helpful way of being part of the conversation.

An important part of this is the mentor needs to see themselves as a learner as much as the others in the conversation. This in turn can influence others to be more open to learning and less dependent on outside expertise. In the T-group story above, I eventually, listened to my heart, realized that the group was uninterested in my process comments, and opened myself to the experience of being with what is happening at the moment. Being in the moment led me into what turned out to be quite profound relationships.

We may not always be in mentoring mode. We may be more of a technical expert hoping to fix a problem that is sufficiently similar across contexts that we can just offer good advice. The kind of mentoring I am describing above is helpful if you are intending to help someone with the kind of learning that links the personal, the organizational, and the social as is often required when working for inclusion and gender equality. As I was reminded by Nkechi, this kind of mentoring acknowledges that individuals and organizations hold the required expertise to solve systemic problems around them and should be encouraged to take the lead in unraveling answers to problems they face rather than looking for outside expertise.

This blog post was written by David Kelleher, Gender at Work Senior Associate.